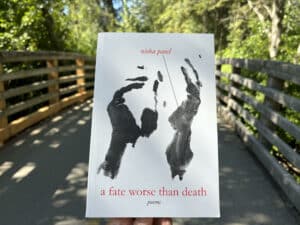

Book review: poems of deep connection, acceptance, and hope

Patel lives with multiple disabilities — treatment-resistant diabetes, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and complex chronic pain — which are investigated through visual poetry, drawings, x-rays, and medical reports that lay bare the absurdities, expense, and indignities of seeking care for chronic illnesses.

In “Portrait of the Artist” Patel eviscerates the nonsensical rules around accessing life-saving drugs. “it gets so quiet that I think the pharmacist who gives me emergency salbutamol but only thirty days of lorazepam (see: benzos are bad controlled substances) thinks there is a good and a bad way to die”

A series of blackout poems — in which words are blacked out from Patel’s actual medical reports from visits to a university mental health centre—are brief, clinical, and cold in referencing Patel’s depression and distress.

In the poem “83” we see how cruel and bewildering the onset of bipolar disorder is, which cause dramatic mood swings and affect a person’s ability to function, often in the late teens and early twenties. For Patel, high school was a land of promise, of being voted Student Union President, of future potential careers, and living in a body she loved. In university, Patel’s former life has become one of innumerable medical appointments, tests and evaluations. On an Emotional Regulation Handout, there is a list of 229 Pleasant Events. Few are selected, and “83. planning parties” is not one of them; it’s an event she once enjoyed, and was good at.

In an astonishing poem “the curse of the Kohinoor” Patel deftly draws a line from the effect of colonial starvation and epigenetics to the shortened lives of her family. She compares the weight of the cursed Kohinoor diamond, “forced” into the Queen’s crown by the British East India Company, to the weight of her own family’s failing organs.

but I know

it weights one-fourth of my pancreas

six days of insulin,

and one-fifteenth of my grandfather’s failing heart

One of the explored tensions in the collection is Patel’s desire to both end her body, and ultimately, to love her body, despite the incessant insults and pain she endures. While it may be impossible to truly understand a disability we don’t live with, (and acknowledging every person lives with specific diseases and disabilities differently) Patel deftly transported this reader to a place of deep connection and empathy, and an appreciation of her ultimate perspective of hope, love and acceptance.

In the poem “I learn that I am Disabled” she writes,

“that in an accepting society we are all a little disabled

but no one is told they are less

no one is left wanting more”

Nisha Patel is a Poet Laureate Emeritus of the City of Edmonton and a Canadian Poetry Slam Champion.

She will be appearing in The Sound of Story reading event on Oct. 17 and teaching a creative writing workshop Outside the Docx: Visual Design in Poetry on Oct. 19 at the Whistler Writers Festival. Tickets are on sale now.

Rebecca Wood Barrett is a filmmaker and writer living in Whistler, BC who lives with insulin dependent diabetes. Her children’s chapter book My Best Friend is Extinct won the Chocolate Lily Book award, and her follow-up book My Summer Camp has Mega Sloths will publish in May 2025.