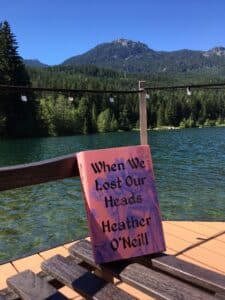

O'Neill's newest novel sticks with you long after you're done reading

Marie Antoine is the daughter of the richest man in 19th century Montreal. Her face is printed on the bags of sugar her father’s factory produces and she wants for nothing, except maybe her dead mother — but not even that really. She bores easily, and lives to be the centre of attention. Her blasé world is turned upside down when Sadie Arnett, the daughter of ruthless social climbers (her father is a politician), moves into the neighbourhood. Sadie is skeptical, cynical, and a peculiar thinker. She’s not like other girls Marie has befriended.

The girls are drawn to each other and forge a deep bond almost immediately. O’Neill perfectly captures the rawness, vulnerability, and weird intensity of close childhood friendships. Both these girls have a hole in their hearts and they use each other to fill it up. So, of course, fate (and their choices) intervene and they are separated and left to grow up apart, nursing the memories and their grievances.

If anyone has thought that maybe little girls are a little darker than we give them credit for, this book reinforces that idea, but also expounds on the implications of ignoring what girls, and women, are capable of when pushed to the brink by gender expectations, society, and the patriarchy.

Ultimately, this is a story about power — who has it, who doesn’t, how to get it, how to lose it, and where it come from — told from the perspective of women from different social classes who each struggle with being a woman and its limitations, and what they might instead choose for themselves if they had half a chance. Sadie and Marie are the impetus for the change around them, and their actions spread in a chaotic wave through the city.

I like how O’Neill isn’t afraid to write about women behaving badly (at least by the expectations of the day and setting). Her characters seem to have a bonhomie attitude about the damage they’re causing that I appreciate. They make the choices they can live with — no explanation or excuses needed. It makes the characters stronger.

Women resort to poison, to job action, to tormenting their male overseers, to writing pornography, to stirring up discontent as the characters who are impacted by Marie and Sadie’s choices strike out to make a life for themselves. The true villains are societal norms and the patriarchy. Marie and Sadie are selfish, but it’s easy to empathize — they’re no freer and don’t have much better choices than anyone else, and they act accordingly. Things can be beautiful and destructive at the same time. The fight for a better and more equitable life usually leaves some bodies behind. O’Neill writes accordingly.

Heather O’Neill is at the Sunday Book Talk: Coffee and Conversation Oct. 16 at 11 a.m. at the Fairmont Chateau Whistler and online.